What is it all about? Why should one study FM?? Here’s a quick introduction video on Financial Management from both Curriculum & real life perspective! by…

With due credits to Visual Capitalist

Basic Principles of Fiscal & Monetary Policy Infographic Courtesy by Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (All due credits)

What is RBI Monetary Policy?Monetary policy is the macroeconomic policy laid down by the Reserve Bank of India. It involves the management of money supply…

This guest blog is contributed by our student Ms. Krina Shah. We are welcoming all you budding finance professionals to come contribute your interesting articles…

Personal finance is defined as the management of money and financial decisions for a person or family including budgeting, investments, retirement planning and investments. Following are some goals…

Till 2000, the budget was presented at 5pm on the last working day of February. It was only in 2001 that finance minister Yashwant Sinha…

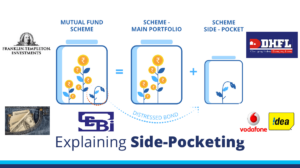

#CorporateDebt #RatingsDowngrade #VodafoneIdea #AGR #MutualFunds #SidePocket Recently Franklin India Ultra Short Bond Fund had written off its entire exposure in Vodafone Idea debt security (~4.3%)…

Land Acquisition Bill Explained in Simple Words: The problem To benefit the society as a whole we need to build large infrastructure projects such as…